‘commitment’ versus evidentiality

Jul 13

appraisal, pragmatics, semantics No Comments

or, why the term ‘commitment’ is already lexically ‘full’ for most linguists who’ve been hit with the psychological stick.

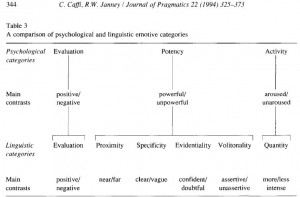

here, below, is a table excerpted from an older article discussing the advances made in the study of affect and emotive v. emotional language at the time: the source is at the top, so no need to reference.[click on the pic for a better image]

it’s notable that for most linguists in the pragmatics tradition (claiming the prague school amongst their antecedents) there has existed a separation between specificity and evidentiality.

the most recent use of the term ‘commitment’ by students of SFL seems more aligned with traditional pragmaticists’ notions of specificity, while for these pragmatic types, ‘commitment’ is a term that is a function of markers of evidentiality, i.e. personal commitment to a position.

while a degree of specificity in language use might also function to signal an individual writer’s degree of commitment to a proposition, my own position on the matter of evidentiality is that it tends to focus attention on the intent of the individual, rather than the social construction of interpersonal relationship (given that both experiential as well as interpersonal meanings are entailed in discourse semantic constructions of such co-positioning) [i feel a sense of irony as i write this].

while many linguists are now taking up the idea that individual psychological ‘processes’ need to be not only factored in but accounted for in any analysis of language – and thus terms which suggest individual psychological focus may be part of a trend – the fact that the use of the term ‘commitment’ seems to straddle two distinctions in traditional discourse analytic approaches may render it immiscible with them.

As is well known, the main linguistic means of commitment in the epistemic modality are Urmson’s (1952) parenthetical verbs, and modal adverbs like ‘probably’, which modify the ‘claim to truth’ of an

assertion. These are called ‘evidentials’ in another tradition. If commitment is defined as a sign of subscription (‘neustic’ in Hare’s terms) (cf. Hare, 1970; Lyons, 1977), then involvement, it seems, could be defined as the emotive subscription to the utterance.

( Caffi&Janney:348)

RSS

RSS

Recent Comments